My boy is two years and four months old. In the last three or so months, he has aged about a year. Every day I realise that he has learned something new, something that I don’t remember teaching him, and I am stunned into silence. Silence, however, is really more of a concept in our house now, as Master Hamish does not like to have his delicate ear so disturbed by that buzzing emptiness of ‘quiet’. Instead, my internal monologue is drowned out by the plaintive narrative of a toddler to whom every second is of vital importance.

“Hamish needs…Hamish needs…bikkit. Cake? Mummy. Mummy. Want Daddy. Where’s Daddy? Daddy go to work today, tap-tap-tap, Daddy not in car, white car, Daddy go do his work up-STAIRS! Up. STAIRS. No boys and girls, no boys and girls today, today is a MUMMY DAY. DAAAAAAAADY. Mummy. Malt loaf? Hamish snatch bin lorry from Theo. Mummy say NO, Hamish, don’t snatch bin lorry. Theo bin lorry. Hamish don’t WANT SHARE.”

During which time, he has attempted to scale the stair gate, been chased away by yours truly, run to the kitchen cupboard to search for illicit snacks, been chased away by yours truly, swung off the kitchen door handle, been chased away by yours truly, and then run away giggling like a maniac, usually with something he shouldn’t have, tightly bundled up in his fist. He’s very fast, and by this point I’m usually flagging and regretting not simply getting knocked up in my teens. I used to be faster then, partly down to youth, and partly because we lived in a rough area where the local kids had a pretty good throwing aim.

Something I have learned from having Hamish, quite apart from certain skills in the fields of tackling and bodily restraint, is that toddlers, a bit like dementia patients, constantly skip between time periods in their heads. Hence why his stream-of-consciousness monologue includes a running tally of foodstuffs that he desires in the present, a description of what his father is currently doing compared to what he did yesterday, and in the same breath a segue into a slightly fractious playdate with his friend Theo a whole ten days prior. Unlike dementia patients, however, when we hand them over to be cared for by minimum-wage migrant workers, we tend to take them back at the end of the day. Usually.

Actually, I feel quite bad making that crack about migrant workers. All of the staff in my son’s nursery are locals with fabulously broad Lancashire accents. Think Victoria Wood, Peter Kay, or Johnny Vegas, if that helps. If you’re American it probably doesn’t help at all, and for that I’m sorry (Lancashire translation: Am sorreh). To help provide an example, please see below for an attempt at embedding a Youtube clip from the wonderful Victoria Wood show, “Dinnerladies”. Full episodes are available on Youtube, and possibly Netflix.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="

title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Despite only being under the care of nursery staff for a grand total of 12 hours per week, my son’s accent is already skewing heavily Lancastrian. In all fairness, he also spends about the same amount of time with my parents-in-law, both of whom enjoy chewing their vowels in the local tradition. It’s an odd dialect, utterly lyrical and soothing on one person, harsh and miserable on another. As with the English language itself, it has many idiosyncrasies that simply need to be learned by exposure, rather than memorised by rote. “Cake” is pronounced more like “cairke”, long and drawn-out in the middle. On the other hand, “take” must be cut down to size and spat out thus: “tek”.

Hypocrite that I am, I rail against the loss of linguistic heritage and local accents, all while trying to get my son to adopt a southern “u”. Up instead of up. Easier said than written. I’m beginning to suspect that I have a chip on my shoulder about how my family and I appear to other people. I’m essentially a working-class snob, proud and self-loathing in equal measure. I identify as trans-class; I’m a minor aristocrat trapped in the body of an admin assistant. I like to joke that I’m from the finest council estate in all of Hertfordshire. It could be worse, I could, like Lewis Hamilton once did, to much uproar, claim to be from “the slums” of Stevenage, the same respectable and well-to-do Hertfordshire town in which I was born.

Council estates? Yes.

Slums? No.

The fact is that we form an instant impression of somebody based on their appearance, manner of speaking, and general demeanour. No matter how pure of heart you try to be, dear friends, we are pattern-recognising animals. I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing, either, as long as you are willing to change your mind when necessary. Either way, my accent has long made me stand out in my local area and has encouraged people to form particular opinions about me, both good and bad.

A shy, bookish tomboy as a little girl, I was often singled out further by being incorrectly identified as “the Australian”, “the posh girl”, and on one occasion, “an ignorant French person”, by my childhood peers. To be an outsider is difficult at times. To be accused of “poshness” by angry kids with the same class background as you is just plain frustrating. It is even worse when they are several rungs above you on the money ladder.

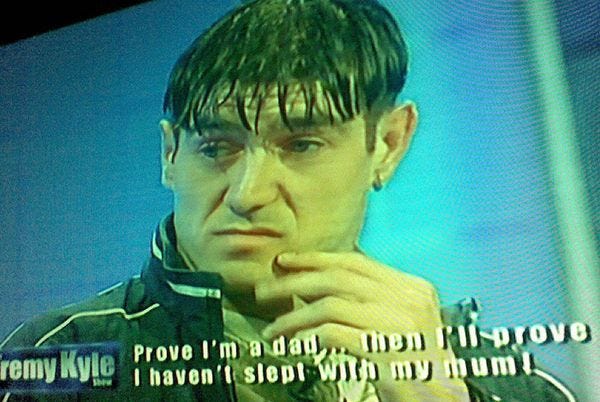

Between the ages of 11 and 18, I attended a Grammar School. There, I encountered Actually Posh girls, girls with true toffee accents who went skiing yearly and whom I must say were all lovely. There were a handful of working-class girls, all of them with strong local accents, and not a single fuck to give between them. The rest were somewhere in the middle, both with regards to accent and money. It was a middle-class girl whose parents were high-earning professionals that owned several ponies that called me “posh” one day. At the time, my mother was a cleaner. My father was a salesman who was threatening to move to Sri Lanka to try to avoid paying child support. We lived in a small terraced house next door to people who had been on the Jeremy Kyle show. I was surprised by her characterisation of me, to say the least.

I tried for a while to push my voice into the local mould. It didn’t work. I could keep it up for a short while, for example while giving lip back to the teenagers in my neighbourhood and pretending not to be petrified that they were going to knife me or forcibly apply 14 layers of orange foundation to my freckled face. I just couldn’t be convincing for longer than a few minutes at a time, so I gave up. I let people indulge in whatever ideas they hold about me, and I learned to accept the good and bad that comes of it.

Of course, there is a positive to it. While I acknowledge that it is not fair, and I can easily shatter their illusions with just a few minutes of talking, some people think that I am smart, or well-bred in some manner. That likely only works in particular parts of the North. If I went to Hertfordshire, they’d think I was a Northern yokel. They would never guess that I was actually from the slums of Stevenage. But up here, it’s enough to make me sound like something I’m not. It’s enough to make people take me more seriously than they would do if I sounded like Johnny Vegas’ drag persona (Jeannie Vag-ass?).

I have learned my accent primarily from my mother. She mocks me when my vowels skew to the north, but equally mocks me when she thinks I sound too “posh”, or God forbid, “too Essex”. I know, I’m sorry. Essex people get all the worst mockery, and only some of it is deserved.

My mother grew up in Stevenage, born to a Lancashire mother and a Perthshire Scot father. They both came from the traditional “work-your-fingers-to-the-bone” type of working-class background. That of scrubbed front doorsteps and frayed clothes mended until they were more stitch than cloth. Respectability was key, and my mother quickly learned that the “right voice” earned you more respect.

She snipped her vowels and kept her diction clear. Combined with a good work ethic and appropriate level of talent, it served her well in her secretarial career. She had to be a secretary, rather than a nurse – the other option for a smart but poor girl – owing to her fear of gore and love of language, both of which I have inherited.

Throughout her life, she has held down a variety of jobs. As previously mentioned, secretarial work features prominently on her CV, but she has also worked as a cleaner and as a support worker for people with brain injuries. As a cleaner and support worker, she had several encounters with people in better paid jobs who assumed, wrongly, that she was stupid. Worse, still, that because she must be stupid, she must be ill-deserving of respect. As soon as she began speaking, those people’s attitudes would change. Partly, this was due to the content of her speech, but I firmly believe that it was in part due to her elocution. Being able to enunciate your consonants and cut your vowels to a near-RP level of clarity can be a valuable weapon against those who seek to diminish your status.

It is decidedly unfair. But I admit to harbouring some of the same prejudice, and with good reason. We notice patterns. We use past experiences to make quick judgements of others, and they are often correct. This leaves me with the realisation that the way I speak is an important part of my public presentation, albeit one that I cannot control as easily as, say, my clothing. It signals my belonging, or lack thereof, to each group that I find myself amongst. This, perhaps, is the real reason why I find myself concerned and conflicted about my son’s speech.

I am a Nobody and a Somewhere, who could have been an Anybody and an Anywhere, and who is rejected by so many Somewhere’s. Have I lost you yet? My family has moved about the British Isles over the generations, ping-ponging from one corner to another. Unlike my husband, who can trace his family tree back six centuries and can see its roots clearly confined to a three-mile radius, I feel strangely untethered.

My voice has often acted as a signal to the locals that I am a foreigner, and some of my strongest early memories are of being keenly aware of the rejection and loneliness that came with it. I grew up without much extended family nearby and never really felt that I belonged to the area, despite my fierce love for my adopted hometown and county.

I have no desire for my son to be left out, or to feel ridiculed or estranged from his peers. However, I also cannot stand the thought of him being looked down on or pigeon-holed in some manner. I cringe when I hear myself “correcting” the way he says “up” or “bucket”. I think that perhaps the best thing to do would be to allow him to find his own voice, cringeworthy though that phrase may be. In whatever manner he speaks, people will still pass judgements, some will mock or ostracise him, others will respect and love him. I cannot protect him from being human, and to smother him would be a failing on my part. And if all else fails, he can always become a mime.

It's fascinating to me how much there is to say on classism, still, in your corner of the world. So many strong identities across such a relatively small distance!

Hamish's monologue made me smile!

There was a time when my son talked like Teletubbies and another when my daughter talked like Peppa Pig. Eventually they go back to Mom and Dad's accent because that's who they identify with.

Have to comment. I wonder if I’m the only American who does-not-give-a-fuck what anybody’s accent is. I truly don’t; further, being of simple means myself would much rather be in the company of the poorer, economically. They at least, are real. I’ve found that the others, are not. Rest your concerns.